In a quiet corner of an industrial district, far from the glamorous runways of Paris and Milan, an unassuming studio is quietly unraveling the very fabric of fashion. The phrase "knit one, purl two" takes on a radical new meaning here, where the gentle click-clack of needles is accompanied by the whir of power tools. This is the home of a movement that defiantly declares: everything is knittable. Even, astonishingly, car parts.

The studio, known simply as Interloop Atelier, doesn’t look like a typical fashion workshop. Instead of bolts of silk and chiffon, the space is dotted with deconstructed automobile components: engine blocks stripped bare, gearboxes sitting like sculptures on workbenches, and piles of spark plugs, pistons, and wiring harnesses that look more like industrial scrap than potential garments. Yet, under the visionary direction of lead designer Elara Vance, these metallic, greasy, and rigid objects are being transformed into stunning, wearable art.

Vance, a former automotive engineer with a degree in textiles, founded Interloop three years ago after a moment of epiphany in a junkyard. "I was looking at a crumpled car door," she recalls, "and instead of seeing wreckage, I saw a canvas. The lines, the curves, the material memory—it felt like a narrative waiting to be rewoven, quite literally." This philosophy drives every project at the studio. It’s not about upcycling for the sake of sustainability alone, though that is a significant benefit. It’s about challenging the very definitions of material, craft, and beauty.

The process begins with what Vance calls "material translation." Car parts are not simply sewn onto fabric; they are deconstructed and re-engineered to become the yarn itself. Aluminum from engine blocks is melted and drawn into fine, flexible wire. Rubber from tires is shredded and spun with organic cotton to create a durable, elastic blend. Even glass from windshields is crushed and fused into bead-like elements that catch the light. "We’re not just using these materials; we’re communicating their history," Vance explains. "The knit structure allows for that storytelling—each loop and stitch can vary in density, texture, and strength, mirroring the part’s original function."

One of the studio’s most striking pieces is a gown crafted from the wiring harness of a vintage sports car. The copper filaments within the wires were extracted, coated for safety, and knitted into a bodice that drapes like chainmail but glows with a warm, metallic sheen. The skirt incorporates the plastic insulation, softened and blended with hemp, creating a surprising fluidity. It’s a garment that embodies paradox: both heavy and light, both industrial and delicate, both past and future.

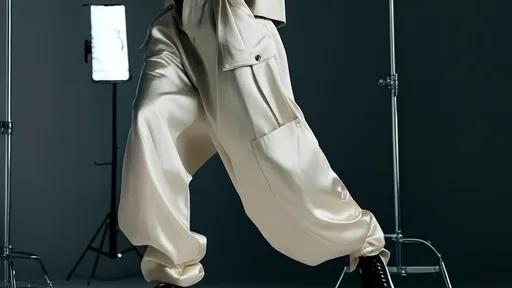

Another piece, a structured jacket made from reformed steel car panels, required the team to develop a entirely new technique. "We couldn’t knit steel like wool," says Marcus Thorne, the studio’s materials technician. "So we laser-cut the steel into micro-strips, then used a specialized loom to weave them into a pliable mesh. It moves like leather but has the presence of armor." The result is a garment that whispers of resilience and protection, a direct nod to the car’s primary purpose of safety.

The challenges are immense. Knitting with unconventional materials requires custom-built tools and endless experimentation. Tension, gauge, and needle strength must be recalibrated for each new material. "We break a lot of needles," Thorne admits with a laugh. "But every failure teaches us something. You can’t be afraid to snap a few things when you’re making something that’s never existed before."

Beyond the technical marvels, the work at Interloop Atelier raises profound questions about consumption and creativity. In an era of fast fashion and environmental crisis, Vance’s approach is a bold statement against disposability. "Cars are designed for longevity, for decades of use. Fashion is often seen as ephemeral," she notes. "By merging the two, we’re asking: can clothing carry the same weight of durability and purpose? Can a dress be built like a car?"

The studio’s work has not gone unnoticed. While some in the fashion industry initially dismissed it as a gimmick, others have embraced its innovation. Interloop has collaborated with avant-garde designers and even automotive brands looking to explore sustainable branding. Their pieces have been exhibited in art galleries and tech conferences, blurring the lines between craft, engineering, and environmental art.

Yet, for all its high-concept appeal, the studio remains deeply connected to the handmade. Each piece is produced in limited editions, often taking weeks or months to complete. The knitters and technicians work with meticulous care, their hands guiding materials that have never been handled this way before. There is a palpable reverence in the process—a sense that with each stitch, they are not just making a garment, but mending a disconnect between human ingenuity and the material world we often discard.

Looking ahead, Vance dreams of expanding the "everything is knittable" ethos to other domains. "Imagine knitting with medical waste, or with data storage devices, or with construction debris," she muses. "Every material has a story and a potential second life. Knitting is just the language we use to tell that story."

In the end, Interloop Atelier is more than a studio; it’s a manifesto. In a world overwhelmed by waste and sameness, it offers a vision of creativity that is both resourceful and revolutionary. Here, a spark plug isn’t just a spark plug—it’s a potential button on a coat. A piston isn’t just a piston—it’s the centerpiece of a necklace. And a car isn’t just a car—it’s a wardrobe waiting to be unraveled and rewoven, one stitch at a time.

By /Aug 21, 2025

By /Aug 21, 2025

By /Aug 21, 2025

By /Aug 21, 2025

By /Aug 21, 2025

By /Aug 21, 2025

By /Aug 21, 2025

By /Aug 21, 2025

By /Aug 21, 2025

By /Aug 21, 2025

By /Aug 21, 2025

By /Aug 21, 2025

By /Aug 21, 2025

By /Aug 21, 2025

By /Aug 21, 2025

By /Aug 21, 2025

By /Aug 21, 2025

By /Aug 21, 2025

By /Aug 21, 2025

By /Aug 21, 2025