In the ever-evolving landscape of fashion and design, a curious trend has taken root, one that marries the cutting-edge with the archaic, the high-definition with the deliberately distorted. This movement, known broadly as Digital Nostalgia, is not merely a fleeting fascination but a profound cultural shift, a yearning for the tactile and the imperfect in an increasingly polished and virtual world. It is a visual language spoken through the gritty texture of low-pixel prints and the hypnotic glow of CRT screen colours, a language that resonates deeply with a generation caught between the analog past and the digital future.

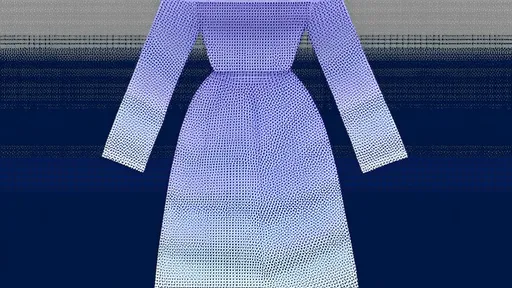

The aesthetic of low-resolution imagery, once a technological limitation to be overcome, has been wholeheartedly embraced as a deliberate stylistic choice. Designers are now scavenging the digital archives of the late 20th and early 21st centuries, pulling forth blocky, pixelated graphics from early video games, primitive computer interfaces, and the first blurry JPEGs shared over dial-up modems. These images are then blown up, distorted, and printed onto fabrics, creating garments that wear their digital origins not as a flaw, but as a badge of honour. A sweatshirt might feature a massively enlarged, jagged icon from a 1995 operating system; a dress might be adorned with a cascading pattern of glitched, corrupted data. This is not about replicating the past with perfect accuracy, but rather about re-contextualising its visual artefacts, celebrating the charming clumsiness of early digital expression.

This celebration of the low-fi is intrinsically linked to the physical media that first displayed it. The Cathode Ray Tube (CRT) monitor, with its distinctive convex glass and deep chassis, is the undisputed muse for this colour palette. The colours emitted by these screens possessed a unique vibrancy and character that modern LCDs and OLEDs, for all their technical precision, have failed to replicate. There was a certain warmth to the glow, a slight blur at the edges of pixels, and a mesmerising scanline effect that sliced across the image. Fashion’s adoption of this palette means embracing these very qualities: electric blues that hum with energy, saturated magentas that bleed slightly into adjacent colours, and phosphor greens that seem to vibrate against darker backgrounds. It’s a palette that feels alive, slightly unstable, and deeply evocative of a specific moment in technological history.

The cultural driver behind this trend is a powerful sense of nostalgia, but it is a nostalgia filtered through a contemporary lens. For Millennials and older Gen Z, these low-resolution graphics and CRT hues are not distant, historical curiosities; they are the visual backdrop of their childhoods and adolescences. They are the graphics of their first Super Nintendo game, the interface of their family’s first Windows 95 computer, the visual noise of a late-night television broadcast. This trend allows them to wear these memories, to physically embody a time of discovery and nascent digital connectivity. It is a form of identity-making that connects personal history with aesthetic expression, a way of saying, "I was there when it all began."

Furthermore, this movement is a conscious reaction against the sleek, often sterile, perfection of today's high-definition world. In an era of 4K resolution, flawless CGI, and algorithmically smoothed Instagram feeds, the gritty, imperfect, and sometimes downright ugly aesthetic of digital antiquity offers a refreshing counterpoint. It feels more human, more authentic. The visible pixels, the colour bleed, the scan lines—these are all traces of the machine's struggle to render an image, a struggle that has been entirely erased by contemporary technology. By incorporating these "flaws" into fashion, designers and consumers are pushing back against a culture of seamless perfection, opting instead for something with more texture, more history, and more soul.

The application of these concepts on the runway and in streetwear has been remarkably diverse. High-fashion houses have sent models down the catwalk in dresses printed with distorted, low-polygon renders, their fabrics mimicking the shimmer of a screen catching the light. Streetwear brands have released entire collections centred around themes of "cyber nostalgia," featuring pixel-art logos and gradients that perfectly capture the transition of a sunset on an old VGA monitor. Accessories, too, have joined the fray, with bags and shoes featuring hardware that mimics the bulky buttons of a vintage mouse or the grating of an old computer speaker. The trend has proven to be incredibly versatile, easily adapting to everything from avant-garde haute couture to accessible casual wear.

Looking forward, the principles of Digital Nostalgia seem poised to evolve beyond mere aesthetic homage. As the tools of creation become more advanced, we are beginning to see designers use AI and complex algorithms not to create hyper-realistic imagery, but to simulate and exaggerate the artefacts of older technologies. Imagine fabrics woven with patterns generated by glitch art algorithms, or dyes developed to chemically replicate the specific colour emission of phosphorus. The future of this trend may lie in a deeper, more material integration of its core concepts, moving beyond print and into the very structure of the textiles themselves. It is a testament to the enduring power of these early digital visuals that they continue to inspire such innovation and creativity.

In essence, the fashion world's fascination with low-pixel印花 and CRT screen colours is far more than a retro revival. It is a complex dialogue between past and present, a critique of modern perfection, and a wearable archive of personal and collective memory. By draping ourselves in the visual language of a not-so-distant past, we are not just making a style statement; we are engaging in a form of techno-romanticism, cherishing the beautiful, flawed, and profoundly human beginnings of our digital age.

By /Aug 21, 2025

By /Aug 21, 2025

By /Aug 21, 2025

By /Aug 21, 2025

By /Aug 21, 2025

By /Aug 21, 2025

By /Aug 21, 2025

By /Aug 21, 2025

By /Aug 21, 2025

By /Aug 21, 2025

By /Aug 21, 2025

By /Aug 21, 2025

By /Aug 21, 2025

By /Aug 21, 2025

By /Aug 21, 2025

By /Aug 21, 2025

By /Aug 21, 2025

By /Aug 21, 2025

By /Aug 21, 2025

By /Aug 21, 2025